Published: : April 7, 2025, 04:49 PM

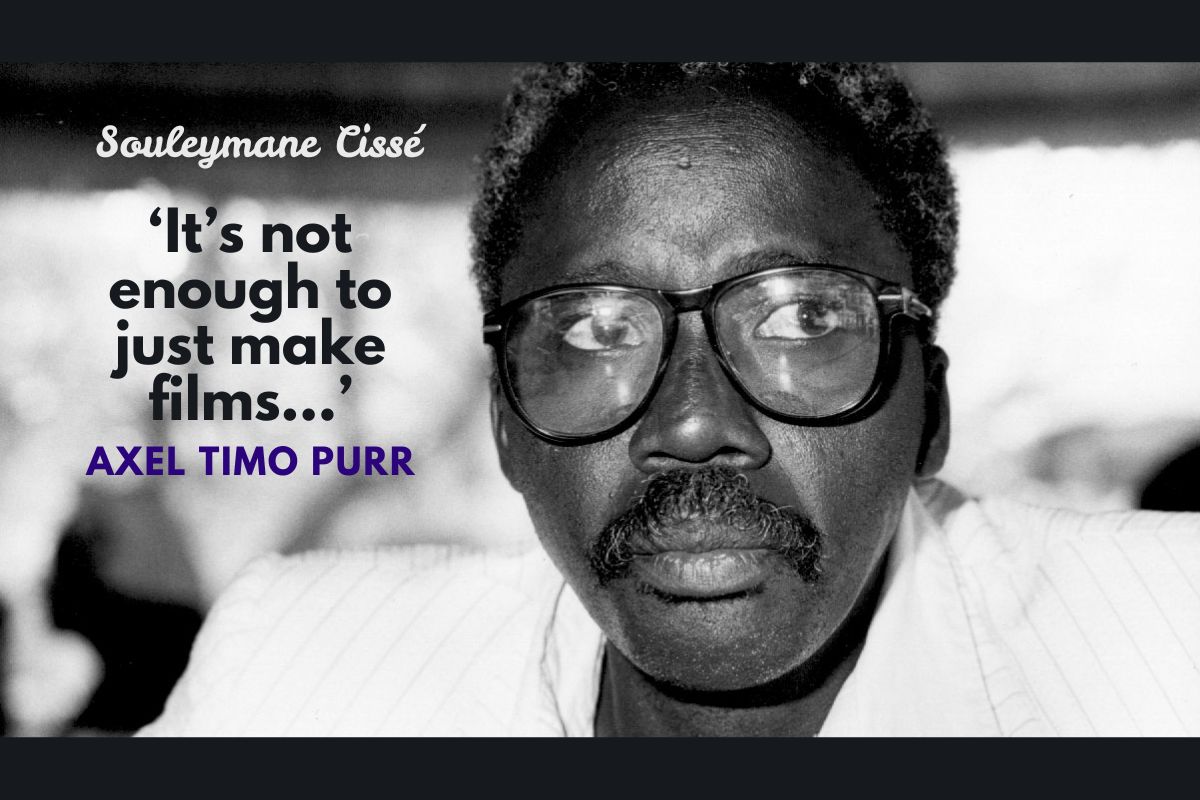

Souleymane Cissé, Cannes winner and one of the great ‘African’ filmmakers of the first generation, has died in Bamako at the age of 84. On his deathbed, he appealed to the government of his home country to support Mali’s cinema

It is not easy to receive the recognition you deserve as a filmmaker in one of Africa’s most diverse cultural regions. When the great Nigerian director and producer Eddie Ugbomah, without whom contemporary Nigerian cinema would be unthinkable, fell seriously ill in 2019 and died shortly afterwards, not even a desperate appeal for donations to pay for his medical expenses had any effect.

In the case of Souleymane Cissé, who many consider to be the greatest African filmmaker of all time not only because of his successes in Cannes, it was the ‘Carrosse d’Or’ awarded to Cissé in Cannes in 2023 for his innovative life’s work, which disappeared from his house in Bamako in 2024 and had to be reported stolen, causing great consternation among the Malian public, even though the prize has remained missing to this day.

But at least Cissé still has a monument in Bamako commemorating his work and a career in film spanning over 50 years, which actually lasted much longer, because Cissé, who was born in Bamako and grew up in a Muslim family, was a passionate cinema lover from childhood and attended cinemas in Bamako and also Dakar, where he attended secondary school, from which he only returned to Mali in 1960, the year his homeland gained independence.

His ‘adult’ film career began when, as an assistant projectionist on a documentary about the arrest of Patrice Lumumba, he was so enthusiastic about the material shown and the social realism that all the enthusiasm awakened in him the desire to make his own films. He was awarded a scholarship at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography, the Moscow School of Cinema and Television, and returned to Mali in 1970 to work as a cameraman at the Ministry of Information, producing documentaries and short films.

Two years later, Cissé made his first medium-length film, Cinq jours d’une vie (Five Days in a Life), which tells the story of a young man who drops out of a Koranic school to live on the streets as a petty thug.

In 1974, Cissé produced his first feature-length film in Bambara, the lingua franca of Mali. Den Muso (The Girl) is the story of a young mute girl who is raped. The girl becomes pregnant and is rejected by both her family and the child’s father. Den Muso was banned by the Malian Minister of Culture and Cissé was arrested and interned on corruption charges - he had allegedly accepted French funding. But Cissé was undeterred: during his time in prison, he wrote the screenplay for his next film Baara (Work), which he completed four years later in 1979 and which became his first major success and won numerous awards.

With the tailwind of success, Cissé set about making his next film Finyé (Wind), which tells the story of disaffected Malian youth rebelling against the establishment. For this film, he received his second Yenenga’s Talon at Fespaco in 1983 after Baara in 1979.

Between 1984 and 1987, Cissé worked on Yeelen (Light or Brightness), a coming-of-age film and probably his best-known film in the West, which won the Jury Prize at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival, making it the first African film in the festival’s history to win an award. In an interview for Cahiers du Cinéma, Cissé emphasised that Yeelen was also a statement against European ethnographic film and its Eurocentrism. In 1995, Cissé returned to the Cannes Film Festival with Waati (Time), where his film was in competition for the Palme d’Or.

In 2009, Cissé made the comedy Tell Me Who You Are, in which he thematises polygamy and tells a story that Cissé himself experienced when he, his eight brothers and his sister were forced to leave their home in 1988 under pressure from their own father. His last film O Ka (Our House) was also inspired by his own family dramas; it recalled his sisters‘ legal battle when they were evicted from their home in Bamako.

Souleymane Cissé, the grand old man of West African cinema, died on 19 February 2025 at the age of 84 in a clinic in Bamako. He was supposed to chair the feature film jury at the 29th edition of Fespaco on 22 February in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, but it wasn’t enough for that. But on the day of his death, he still had the strength to remind the Malian military leadership, which had surprisingly declared 2025 to be the year of culture, to support the Malian film industry so that it can keep up with the competition on the continent as it used to:

‘It is not enough to make cinema; the works must also be visible. May the authorities help us to build cinemas. That’s the appeal I’ll make to them before I die, if God wills it.’